By 1960 the population of Hunt County had declined from 48,793 in 1940 to 39,399. The decrease was due to a drop in the White population which went from 42,503 in 1940 to 32,934 in 1960, an indication to the near-disappearance of the small landowning farmer. The Great Depression pushed small farmers off the land even as WWII and Cold War era spending booms created industrial jobs for white workers in cities and towns. During this same time the Black population rose from 6,288 to 6,408.

As more segregationist policies and laws were passed in the early 1900s there were continued efforts by minorities to break down racial barriers. During the 1960s African Americans and Mexican Americans participated in the national movements that were taking place. Black Texans held demonstrations within the state and boycotted segregated stores. In conjunction with the National March on Washington in 1963 approximately 900 protestors, which included Hispanics, Blacks and Whites, marched on the Texas state capital. They were against the slow pace of desegregation in the state and Governor Connally’s opposition to the pending civil rights bill in Washington. The 24th Amendment passed in 1964 barred the poll tax in federal elections and that same year Congress passed the Civil Rights Act outlawing the continued enforcement of Jim Crow laws. Texas followed suit in 1969 by repealing its own separatist statutes. In addition, the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 eliminated local restrictions to voting and required that federal marshals monitor election proceedings.

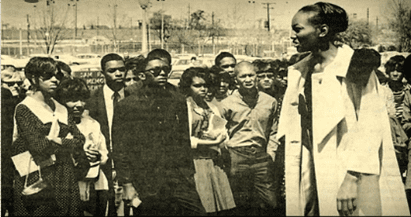

At East Texas State University there were some protests by the students during the 60s. Student protests ran the gamut from demonstrations in favor of racial equality to demands for less restrictive college-enforced female curfews.

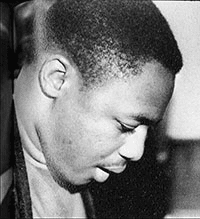

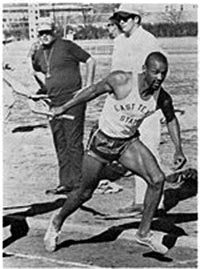

When John Carlos and Joe Tave arrived at East Texas State University (ETSU) in 1966, the community had just begun the process of desegregation. Jim Crow’s impact remained strikingly present in everyday life across this sparsely populated area located approximately one hour east of Dallas, just as it did most everywhere across the American South at that time. Carlos was a sprinter from Harlem who would later become best known for his participation in the Silent Protest in Mexico City in 1968. Tave was a political science major raised in one of the area’s segregated communities. Just as he had in his hometown of nearby Mineola, Tave quickly took on leadership roles at ETSU, especially where such positions brought him together with others equally committed to racial justice.

Unlike Tave, however, Carlos had no first-hand experiences with segregation to prepare him for the injustices he and his young family would face. This sprinter from Harlem was enlightened by Malcolm X, who spoke regularly at the mosque in his neighborhood and from whom Carlos often sought advice. At ETSU, Carlos turned the attention his athletic prowess attracted from the local press into a forum through which to challenge ongoing inequities. Though he would ultimately leave ETSU after only a year, he credits the racial tensions that forced him from this area with inspiring his involvement the next year with one of the most memorable social justice efforts in sports history as he stood atop the medal stand in Mexico City.

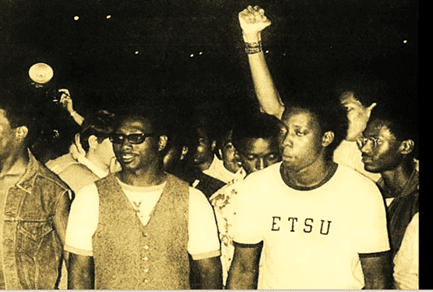

Tave was also inspired by civil rights leaders like Malcolm X, whose presence was felt in every American town with a television, radio, telephone, newspaper stand, or postal delivery. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s influence on Tave is far more obvious, however. Decades later, Carlos would say of his friend, with great admiration, “I always called Joe Tave the ‘MLK of East Texas.” He called himself the “Malcolm X of East Texas.” On the night of MLK’s assassination, Joe Tave established the Afro-American Students Society of East Texas (ASSET), an activist group that helped usher in unprecedented change across the campus and community.

Unlike Carlos, Tave anticipated many of the problems encountered as the American South attempted to remake itself. He knew exactly what it was like to be turned away from restaurants, forced into poorly equipped, overcrowded classrooms with textbooks discarded from the White school. However, this familiarity did not breed passive acceptance. Tave, like Carlos, fought for social justice his entire life. If the campus administration had not responded to ASSET’s “Declaration of Rights,” they were prepared to take more drastic measures. As Tave explained, “[t]hese twins knew the new computer system very well, which had just recently taken over many of the university’s key operations. If they didn’t listen to us, we knew what to do and we were ready”.

A variety of writings mobilized Tave, Carlos, and other activists with whom they worked. Many of the most influential texts included an article in a national sports magazine where Carlos first encountered the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). In December 1967, as he read about racial inequities experienced by student athletes around the nation, he was experiencing similar issues at ET. Carlos called attention to the continued discrimination he and other black athletes faced locally and across Texas. In response, the campus called together other black student athletes, who refuted Carlos’ sentiments.

On the night of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s (MLK) assassination, Tave began writing ASSET’s “Declaration of Rights,” which listed fourteen concerns of African American students in areas which included demands for equal treatment in housing, course offerings in African American history and literature, the employment of African American faculty members, equal treatment of student-athletes, and the withdrawal of University support for racist organizations and events. The “Declaration” was signed by over 100 students and presented to ETSU president D. Whitney Halladay weeks later, followed almost immediately by a public statement by Halladay in which he addressed each of the key concerns and promised action. Their efforts ultimately resulted in the first African American faculty member and administrator being hired in 1968. Similarly, the proportion of female faculty members grew from 20% in 1975 to almost 26% in 1990, and the first woman to hold a high-level academic office was promoted in 1987.[1]

[1] Remixing Rural Texas: A Digital Humanities Project

Installed on July 7, 1921, the sign near the Katy Railway Station originally read “Greenville Welcome – The Blackest Land, The Whitest People.” Realtor William Harrison had created the phrase for his business cards in the early 1900s. In 1916, Harrison was in Kansas City at the same time President Wilson was. Harrison had his business card delivered to the president’s room whereupon Wilson invited him up for an audience. Greenville leaders quickly began using that phrase for advertising which culminated in the new sign that appeared over Lee St. While the “Blackest Land” phrase is generally agreed to have meant the black soil that is synonymous with this area the “Whitest People” phrase has a more complicated history. While the phrase “The Whitest People” may not have started out in a deliberately racist vein there was some context to it, especially once 600 members of the Ku Klux Klan marched through downtown Greenville underneath the sign on December 16, 1921. Their event was the largest in the North Texas area for many years. In 1968, four years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, “Whitest” was changed to “Greatest” and then the sign was removed in 1969.

With the passing of Brown vs. Board of Education (1954) schools in Hunt County were integrated by 1967 with Greenville having integrated in 1965. The transition was not easy as remembered by Melva Hill “It was very painful at first. One of the most painful things was probably that female students did not embrace me. And I felt like, you know, you’re a girl, I’m a girl. So, you know, we ought to get along.” And she remembers that not all of the white teachers wanted them there so that was also difficult to deal with.

Recent Comments