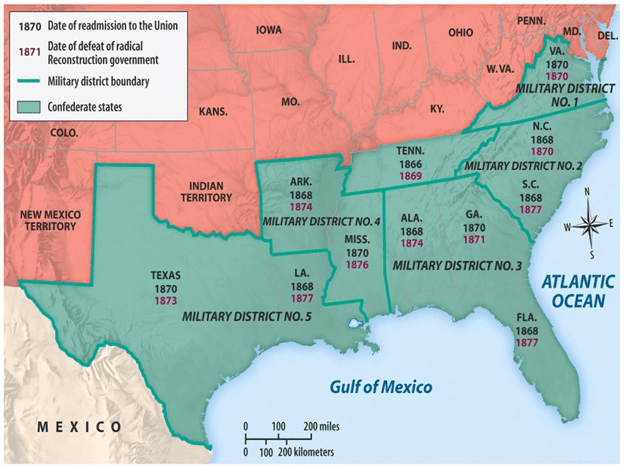

In the aftermath of the Civil War, plans were enacted for the Reconstruction of the Union with the creation of the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865, and the passages of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Reconstruction Act of 1867. Former Confederate States would be presided over by provisional governors who would repeal secession ordinances, frame a new constitution, and repudiate the war debt. Voters would then adopt the convention results and elect a governor and legislators, who would ratify the 13th Amendment (which abolished slavery) to the U.S. Constitution. Texas would not officially re-enter the Union until March, 30, 1870, due to a refusal to ratify either the 13th Amendment (which abolished slavery) or 14th Amendment (which granted citizenship to African Americans).

In the years following the end of the Civil War, the local black population was subjected to many racially motivated acts of violence perpetrated by county whites who were angry over their freedom and political enfranchisement. Even though enslaved blacks had been granted their freedom many Southerners were determined to hinder any social or political progress by the Black populace. At the 1866 Constitutional Convention, Texans imposed restrictive laws known as Black Codes upon African Americans that limited their autonomy. The Codes prevented freedmen from having access to public facilities, imposed curfews, disallowed the possession of firearms or displaying objectionable public behavior (harsh speeches or insulting gestures). Under the codes African Americans without jobs were assigned to White guardians for work without pay. The penalty for quitting often included imprisonment for breach of contract.

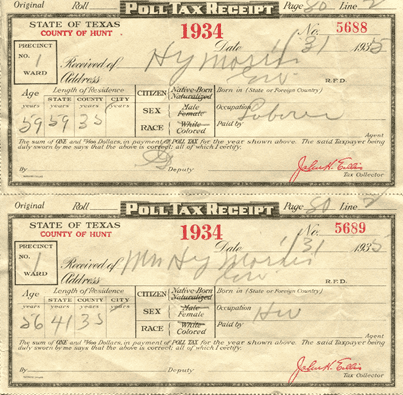

In the 1870’s, Blacks were given the right to vote but in Texas, as in many other places, that right was hampered by Whites who believed that only educated landowners should be able to vote. To restrict Blacks from voting polling places were often initially placed far from Black communities. The roads and bridges to polling places were often blocked on election day and the use of poll taxes, reading comprehension tests, and complicated ballots were further used to keep Black people from voting.

By the 1890’s, Segregation, or separate but equal, had become the norm with the Plessy vs. Ferguson case of 1896 and the Supreme Court upholding a ruling that allowed for “equal but separate accommodations for white and colored races,” though segregation began many decades earlier in the North. The first reference of which is found in the Oct 12th issue of the Salem Gazette in 1838 where there were separate train cars for Blacks and Whites. Despite the daily injustices the Black community faced they developed churches and schools within their own communities and fought for equal rights.

For Hunt County, the Reconstruction Era was a tumultuous time marked by violence. Bad blood between Union and Confederate supporters led to feuds, with the most well-known local one being the Lee-Peacock Feud. This violent, drawn-out fight was led by Unionist Lewis Peacock of nearby Grayson County and ex-Confederate Bob Lee of neighboring Hunt County. The feud took place in the corner’s region of northeast Texas where Grayson, Fannin, Hunt, and Collin counties converged in an area known for its thickets. Bob Lee was raised in the northern part of the thicket and when the Civil War began, he quickly joined the Confederate Army serving in the Ninth Texas Calvary. Lewis Peacock came to Texas in 1856 making his home just south of Pilot Grove, about seven miles away from the Lee family. Peacock helmed the Union League, an organization that worked for the protection of Blacks and Union sympathizers. The conflict that would arise between these neighbors reflected that of the area caused by the Civil War.

Bob Lee fell out with the Union authorities and aroused the enmity of Lewis Peacock, one of their supporters. There are differing accounts of how the feud began with one being that Peacock saw Lee as a threat to reconstruction and came up with the idea of extorting money from Lee to circumvent this. Lewis Peacock and a group of his supporters went to Lee’s home to arrest him for alleged war crimes. The group stated that they were taking Lee to Sherman, they stopped in Choctaw Creek bottoms, where they took Lee’s watch, a $20 gold coin and forced him to sign a promissory note for $2000. The Lee’s refused to pay the note, bringing suit in Bonham, Texas, and wining the case although that is not definite as another source stated that the case never went to court and there is no evidence that it did. In addition, other sources state that the entire account never happened. The entire truth of what event began the Lee Peacock feud is most likely lost to history.

Both men gathered their friends and sympathizers and went to war. The feud went on from 1867-1871. Knowledge of the feud traveled as far as Washington D.C. Two companies of federal cavalry were stationed in Greenville in 1868 due largely to the threat posed by this violent feud, with General J.J. Reynolds posting a $1000 reward for the capture of Bob Lee. There would be killing on both sides; Bob Lee was waylaid and killed in Fannin County near the present-day town of Leonard in 1869. A systematic hunt for Lee’s friends and supporters was then begun, with several being killed. Lewis Peacock was shot dead on June 13, 1871, bringing an end to the bloody feud. Fifty men were killed during this feud and many others were injured. Friends and even members of the same family were turned against each other, often with violent and deadly outcomes.

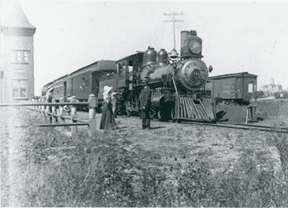

Economics in the county shifted during this time period due to the railroad. In the fall of 1880 the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Extensions Railway arrived in Greenville. More railways would arrive in the coming years. This would transform the county into a more diverse place with more connections to the rest of Texas and the country. The population of the county grew quickly, being nearly 7 times the size it was at the beginning of the Civil War. Greenville would become a rail town which would encourage cotton production in Hunt County and stimulate the development of other commercial and financial institutions. By 1884 the town of Greenville had a population of 3000. The community flourished with two weekly newspapers, 15 businesses, 2 banks, cotton gins, flour mills, and an opera house capable of seating 800. The town’s first water works was completed in 1889 and was later purchased by the city. In 1891 Greenville’s municipal government purchased and began operation of an electricity plant which was the first municipally owned electric plant in Texas. By 1892 the town had a population of 5000, the number of businesses had grown to 200 and had a number of new manufacturing establishments including an ice factory, flour and feed mills, a cotton compress and the machine shops of the MKT railroad.

Recent Comments