Some of the first industries that emerged in Hunt County were agriculture and business related. There were multiple hotels. Sawmills were crucial for the spread of dwellings for the early settlers. Prior to settlement of the area, it featured heavily wooded areas of strong oak and bois d’arc wood. These sturdy woods provided lumber that was beneficial not only for dwellings, but for wagon construction.[1]

J. Pinckney Wolfe built a mill near Oyster Creek in the 1870s, which eventually led to the community named Wolfe City.[2] Wagons could carry up to double their weight at 2,500 pounds. Greenville had a wagon factory that was south of downtown where local blacksmiths worked with woodworkers to construct wagon, instead of ordering them from Northern factories.[3] The Armistead and Ende Hardware stores were in the 2600 block of Johnson Street, where locals could purchase farm and hardware goods as well as the Mitchell Wagon or the Studebaker Wagon.[4]

[1] Conrad, Blackland, page 31.

[2] Museum tapestry.

[3] Conrad, Blackland, page 31.

[4] Conrad, Blackland, page 31-33.

Numerous wild horses congregated at the confluence of two streams today known as Cowleach and Caddo Creek. Native Americans caught them and managed to teach them to accept a rider. Some of the tribes used those ponies to drag tall posts for their homes. Historian Carol Taylor ran across a small article in an old newspaper from Clarksville, TX. It seemed that farmers throughout the region would raise donkeys, breed them with wild horses to breed mules. James Hooker, first Probate Judge of Hunt County, supposedly made a small fortune with such breeding. He and his hands then drove them to markets to sell as Missouri Mules. Few if any mules were bred and raised on plantations as it was too expensive to use the valuable cotton land to feed mules.

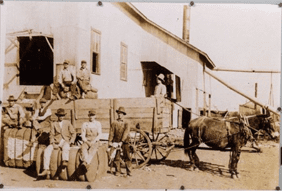

Cotton mills and compresses were crucial to the area after the railroad came to Hunt County. Due to the rich soil of Hunt County cotton grew abundantly and now had a way to get it to market. Greenville’s Compress set a world record on September 30, 1912 for the number of cotton bales pressed at 2,073 bales in ten hours.[2]

[2] Harrison, 231.

https://digitalcollections.smu.edu/digital/collection/jtx/id/903/rec/8. (accessed August 1, 2022).

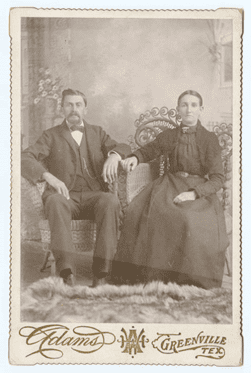

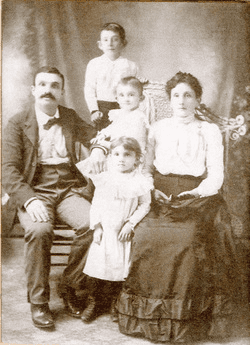

Photography and photographs were a sight to see even at the turn of the twentieth Century. Hunt County featured multiple photographers. William Henry Adams worked as a photographer in Greenville from 1893 until his death in 1936. Photographers would leave an embossed marker of the photographer which also served as a way to advertise their work. John A. Lindgren, a former fireman from Cleburne, opened Knights Gallery in Greenville, Texas in 1895 which remained open until 1900.[1]

[1] Anyjazz, “Cabinet Card Photographers: William Henry Adams,” Cabinet Card Photographers, November 27, 2017, accessed July 9, 2022, http://cabinetcardphotographers.blogspot.com/2017/11/adams.html.

Edward Popper came to Greenville in 1880 after emigrating from Austria-Hungary. He opened a wholesale grocery store at the intersection of Lee and Wesley Streets. Popper’s business was considered “one of the best wholesale houses in north Texas” and helped bring many new business opportunities to Greenville. A local mule-driven transfer company sustained itself by moving goods for Popper’s business, while the store itself provided many residents with jobs. As the cotton industry was growing and becoming increasingly mechanized, K.L. Lowenstein opened a machinery store on South Stonewall Street soon after he arrived in 1881. By 1890 Lowenstein was one of the most successful suppliers of agricultural machinery in north Texas. As the cotton industry continued to grow, Greenville families had more disposable income. This led to more stores selling luxury goods like the Schwartz’ Ladies Bazaar, opened by Lazar and Sophia Schwartz in 1895.

Sam Glassman and his wife Anna left Russia in 1897, making their way to Greenville in 1900. After being in Greenville one year, Sam Glassman had earned enough money to open a dry goods store on the town square. He began his business career with a small inventory and was eventually able to extend his business interests into hides, furs, and scrap metal. Charles and Al Glassman took over the dry goods store in 1921. It was during their tenure that the business suffered “the most extensive and thorough burglary noted here in years” according to the local newspaper. Thieves used hacksaws to break into the store and caused significant damage and made off with $3,000 worth of the store inventory. This was nothing compared to the damage the Great Depression would bring. Sam Glassman lost everything when the local bank he used went under. The dry good store was closed during the Great Depression, but Al Glassman was able to keep the scrap metal business open and even expanded into rayon and oxygen.

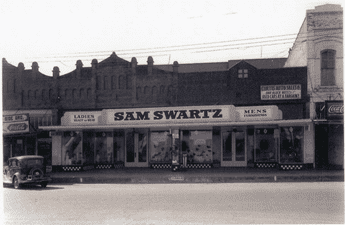

Greenville would also provide Polish immigrant Sam Swartz with a tremendous economic opportunity. In 1919 Swartz opened the Sam Swartz clothing store, housing his family in the back of the small store. Swartz later bought a neighboring building, allowing him the space to expand his clothing inventory. By the time Swartz retired in 1973, the business had expanded to five times its original size. The store employed 25 clerks and department managers and would hire even more during busy retail seasons. Swartz was also one of the only shopkeepers on the town square who, during segregation, allowed Black customers to enter through the front door instead of the back.

Recent Comments