The 1940s

The immediate impact of the Second World War was felt when news of the local deaths of Fred Kenneth Moore of Celeste and James Albert Horner of Caddo Mills were killed during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. U.S. Army Air Corps pilot Truett Majors died the following day, and the city honored him by naming the new airfield after him.[1]

Citizens began doing their part through rationing, war salvaging drives, buying bonds, and joining military service. Employees of East Texas State Teacher’s College (now Texas A&M University – Commerce) were encouraged to sign a pledge to invest in the war effort by buying war bonds.[2] ETSU Students were also encouraged to buy stamps each week.[3] The university offered courses in military training in Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), Civilian Pilot Training, and housed the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in Mayo Hall and the East and West Dormitory for girls.[4] The Women’s Army Corps, branch No. 5. ETSTC opened their WAC school March 13, 1943, for military training. Lt. Col. Ronald E. Doan was the commanding officer at ETSTC for the WACs. These women were trained in personal management, business management, record management and keeping.

[1] There are multiple dates for his death. Dec. 8th or Jan. 5, 1942.

[2] 5 Jan. 1942 Letter to ETSU Faculty

[3] Jimmy Roebuck. “East Texas Teachers: College Group Asked to Help U.S. Defense – East

Texas Student Body Urged to Buy Stamps Each Week.” Dallas News, 01/11/1942, I-4.

Velma K. Waters Special Collections at Texas A&M University Commerce

[4] Men and Women in the Armed Forces from Hunt County Texas – WorldWarTwoVeterans.Com (Greenville, Texas: Greenville The American Legion, n.d.), accessed August 8, 2022, https://worldwartwoveterans.org/men-and-women-in-the-armed-forces-from-hunt-county-texas/.

Local communities got involved like the Wolfe City Red Cross that contributed four hundred knitted garments, and 56,648,000 surgical dressings. Downtown Greenville had a segregated United States Service Organizations (USO) and a segregated Downtown Soldier Club that the city supported both with money and local volunteer entertainers.

In 1944 Major Samuel Jolliffe who was commanding officer of the Black soldiers at Majors Field worked for and got an African American USO club opened on Johnson Street.[1] The Black soldiers at Majors Field were assigned to ground transportation duties on the base. The mess halls on the base, which were praised by both soldiers and inspectors as being excellent dining facilities, were staffed extensively by Black soldiers. One Black soldier, Master Sergeant Develous Johnson, was selected to go to Officers’ Candidate School and became a 1st Lieutenant before his death in 1951. There was also a Black baseball team from the base called the “Thunderbolts”. They played the White teams from Majors field as well as teams from other bases.

[1] Men and Women in the Armed Forces from Hunt County Texas – WorldWarTwoVeterans.Com (Greenville, Texas: Greenville The American Legion, n.d.), accessed August 8, 2022, https://worldwartwoveterans.org/men-and-women-in-the-armed-forces-from-hunt-county-texas/.

Although not completed in 1942, the Army chose Majors Field to be a Basic Flying School to train pilots.[1] It became operational on January 5, 1943. The 201st Fighter Squadron of the Mexican Airforce (nicknamed the Aztec Eagles) trained at Majors Field from November 1944 to February 1945 after first going to San Antonio for initial basic training that was done by the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots. The 201st fighter squadron came to finish their training for combat duty in their Republic P-47D Thunderbolts. Lt. Reynaldo Perez Gailardo loved pushing his big fighter plane. When the squadron went to Greenville, he dropped out of formation in his Thunderbolt and buzzed the town – flying right down the main street on the NW side of the courthouse. On landing, he got busted to a desk job. “I was very sad,” he said later in a University of Texas at Austin oral history, “but I knew that I would fly again one day, and I did.” He was shortly reinstated, in time to conclude his training in Texas and go on to advanced training with the rest of the unit.[2]

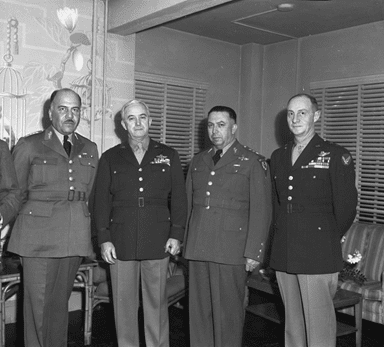

Like many service personnel at Majors Field, the Mexican airmen would travel to downtown Greenville or Dallas for entertainment. Some faced discrimination in Greenville, where they were turned away from one restaurant by a sign that read “No Mexican or Dogs Allowed.” After a public shaming by Col. Herbert M. Newstrom, the restaurant briefly closed then re-opened without the sign.[3] On February 22, 1945, the 201st Fighter Squadron celebrated the completion of combat readiness training with high ranking military officials, such as Lt. Gen. Barton K. Yount, and Mexico’s undersecretary of national defense, Lt. Gen. Francisco L. Urquizo, in attendance. After finishing their training, they went to the Philippines for active duty.

[1] Fred Allison, “Majors Field And Greenville, Texas In World War II”, Pages 2-3.

[3] Fred Allison, “Major Field and Greenville, Texas In World War II”, Pages 182.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries. “Mexican Air Force.” UTA Libraries Digital Gallery. 1945. Accessed July 21, 2022.

https://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/img/20035899

Arriving in the Philippines aboard the U.S.S. Fairisle on April 30, 1945, the 201st was assigned to the U.S. Fifth Air Force. The 201st went into action on its own near Vigan, where the Japanese were dug in. The only way to get them out was to fly close against the mountain range, executing dangerous dive-bombing runs. The Mexican pilots got the job done, to the amazement of the Americans, who nicknamed the Mexicans the “white noses” for the paint on their cowlings. The pilots had to fly so close to the Japanese that one of the first aircraft took “two blows to the wings” according to Vazquez-Lozano.[1]

On June 1, 1945, the 201st planned an attack on a Japanese ammunition depot. Because of three high cliffs and antiaircraft batteries, they would have to dive-bomb from high altitudes and then try to pull their heavy planes up and out. They had never dive-bombed in combat before. They continued to attack Japanese positions day after day into June. They went on to hit remaining Japanese infantry and antiaircraft guns in Northern Luzon and the Marikina Valley, east of Manila. The remaining Mexicans flew dangerous, six hour wave-top missions over nothing but open ocean to hit the Japanese in Formosa with half-ton bombs. “We saw more frequent airplanes from Japan on that 650-mile trip than ever before,” Miguel Moreno Arreola said in a 2003 interview. “But they didn’t want to have combat with us, because they knew our P-47s were better than their Mitsubishis. We could fly higher and faster.” So grueling were these missions that when they returned pilots had to be pried out of their cockpits and helped off the tarmac.

From nearby Guam, the big American bombers roared off to fire-bomb Japan. Despite losses, no replacements came, and with 14 aircraft wrecked, the 201st was becoming ineffective for combat. So many of its pilots were killed and aircraft destroyed that the 201st was left in the Philippines when the U.S. fighters relocated to Okinawa. General Henry Harley Arnold said in 1945 that the 201st squadron put 30,000 Japanese troops out of combat. Logging 2,000 hours of combat sorties, the unit dropped 1,457 bombs on the Japanese. While the 201st didn’t have a major effect on the overall outcome of the war in the Pacific, by the end of the conflict these men were hailed as valiant and deadly in their machines, beloved for their ferocity by the Filipinos and Americans alike. And their participation alongside the Americans helped improve relations between Mexico and the U.S. after the war.

[1] New York Times article.

There were also eighteen British pilots in 1943 that were at Majors Field. In May 1944, there were multiple women pilots of the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) who stayed until the end of the year as they continued their training.[1] The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) served in various functions around the base. Working as clerks and typists they also worked on the flight line as radio mechanics, as air traffic controllers and dispatchers in the control tower, in the Post Hospital and in the Photo Lab.

[1] Fred Allison, “Majors Field And Greenville, Texas In World War II,” pages 157 – 158.

With the Sabine River running right through Hunt County and being one of the primary sources of water the Sabine River Authority became an important part of the counties’ history. The Sabine River Authority was established by the state legislature in 1949 with jurisdiction over all of the Sabine River watershed in Texas. Its responsibilities include controlling, storing, preserving and distributing the waters of the Sabine River and its tributary system. Most important to this region was its first major development in 1956 by entering into a contract with the City of Dallas to build, own, and operate the Iron Bridge Dam and Reservoir (Lake Tawakoni) This project was completed in 1960 and continues to provide water to Dallas, Greenville, Terrell and Wills Point.

Recent Comments